John Wick: Chapter 4 (Chad Stahelski, 2023): 3/5

Wednesday, May 31, 2023

Rye Lane (Raine Allen-Miller, 2023): 3/5

Like a perfectly good Season 2, Episode 3, of one of those shows about neurotic young adults in London. Or, say, Girls.

Sisu (Jalmari Helander, 2023): 3/5

Fun and dumb. Like First Blood but even more cartoonish.

Evil Dead Rise (Lee Cronin, 2023): 2/5

I ask what is ‘evil dead’? A tone? A monster? A series of characteristic camera moves? Certainly the movie doesn’t know. As with Raimi’s recent Doctor Strange movie, I ask “Where is the scrappy and eager amateur Raimi?” In the end, I am just more excited and scared by stuff that pokes at the sticky, bleeding edge than by the competent, even accomplished, presentation of the familiar.

M3GAN (Gerard Johnstone, 2023): 2/5

I don’t really go for killer doll or killer kid movies, and this is no exception.

Tori and Lokita (Luc Dardenne, Jean-Pierre Dardenne, 2022): 3.5/5

Classic Dardennes: a clear-eyed and unsentimental narrative about a character in a bad situation and getting worse. One possible reason for its cool reception is that in the first half, our protagonist, Lokita, is uncharacteristically weak and frightened for a Dardenne protagonist. However, in the second half, we’re more closely tied to Tori, who like a typical Dardenne character is strong and very much on his own trip, sometimes to a fault.

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno (Serge Bromberg, Ruxandra Medrea, 2009): 3.5/5

An insomniac director obsessively pursues his vision. The extant footage of the movie looks stunning. Although she doesn’t have any lines, Romy Schneider has never been better or more alluring.

Ludwig (Luchino Visconti, 1973): 3.5/5

A tour through the madness of the real Ludwig II of Bavaria—symbolized by his palace, with its Escher-like kaleidoscope of wealth, gold and jewels dripping from every surface and furnished with handsome and lusty young men. Mad Ludwig indeed. Ludwig’s extensive patronage of Wagner is especially interesting. Ludwig, Wagner and Visconti share a megalomania, a sense of one’s own nobility, a belief in the compensations of aesthetics, and (between Ludwig and V at least) a fondness for handsome young men. (The lead, Helmut Berger, who just died last week, was Visconti’s lover.) It’s ridiculous that the movie is four hours long, but mad, self-confident excess is the name of the game.

Strike (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925): 3/5

The innovation and editing speed of this movie is astonishing, but they, if anything, decrease emotional engagement—as does the (understandable) focus on the collective over individuals. I’m sure this occurred to Eisenstein (haha), but it’s not very satisfying.

The Bread and Alley, 12 mins (Abbas Kiarostami, 1970): 3/5

A six-year-old deals with a dog on his way home. The opening credits play over a cheery instrumental cover of 'Ob-la-di ob-la-da’ (!!!)

Incoherence, 31 mins (Bong Joon-ho, 1994): 3.5/5

Bad behavior followed by a final irony. I was skeptical that the three stories presented were going to pay off as a whole but damned if they didn’t.

Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946): 4/5

Va-va-voom! Rita Hayworth represents everything desirable, unattainable, unknowable, and possibly loathsome about a beautiful woman—and she’s shot by Rudolph Maté like a goddess. I do wish her acting was as electrifying as her underarms, but you can’t have everything. Glen Ford is ok, but baddie George Macready (and his real face scar) is better. The film reminds one of Casablanca in that it features people who have run away to an exotic location, now waging an internal battle over a powerful and impossible love—as well as in the way it recreates Buenos Aires (and its romantic, WWII-adjacent drama) on the back lot.

7th Heaven (Frank Borzage, 1927): 3.5/5

A dreamy romance between a sewer worker and a young woman abused by her sister, coming to a head with WWI drama. Sets are huge and elaborate, including a seven-story stairwell built so a camera on an elevator can follow the lovers up up up to their seventh-story bit of heaven. Cutie pie Janet Gaynor (5’0”) made 12 films with man-mountain Charles Farrell (6’2”).

Lucky Star (Frank Borzage, 1929): 3.5/5

Reunites Borzage with Gaynor and Farrell and features the same deep, constructed, gnarled, fantasy environments, beautifully lit—not to mention another WWI sequence. In both films Farrell plays a total yokel (which perfectly fits with his broad actorly arm waving) but Gaynor is even more uneducated than he is (not to mention abused), so he seems clever to her. It’s condescending but heartwarming. Farrell returns from WWI in a wheelchair, and he’s such a massive man it’s a shock to see him writhe and crawl on the floor on several occasions to get back in his chair. Both movies end in dumb “Love heals seemingly intractable heath conditions” conclusions.

Yasujirō Ozu Film Fest

A total of Ozu’s 34 movies exist, although 2 are fragments. (I’ve now seen all but one: The Munekata Sisters (1950), which is considered by many to be his worst). Ozu also made an additional 18 movies between 1927 and 1936 that are now lost. A lifelong all-day drinker, Ozu died of cancer on his 60th birthday. Young!!

What you can generally expect from an Ozu movie:

• Great drinking scenes,

• Realistic child characters and actors,

• Flawed fathers,

• The feeling of time passing and the characters’ feelings slowly changing,

• Low camera angles and pillow shots that lend an air of serenity to the drama no matter how serious,

• A frame where everything is equally lit and in focus, from background to foreground,

• A sense of acceptance of life, in all its emotions,

• The best back scratching, neck scratching, arm scratching, and temple scratching in film history,

• Characters who are generous, compassionate, kind and accepting of the weird ways of those around them, and

• Characters who share a cheerful, “all things must pass” attitude, even while tragedy exists.

I loved this viewing project so much that I would like to give half these movies a 5, but I thought it more prudent to give a better idea of my preferences. All these movies are family dramas, which I’ve decided is pretty much my favorite genre (logically, considering the drama of my own life). I find the 14 silent movies here to be surprisingly modern in terms of pace and subject matter. Of course, Ozu made silent movies up until 1935—long after sound technology was available, even in Japan.

Incidentally, Ozu was interested in calligraphy and personally drew all of the main title characters for his color films (at least). He also designed all the bar signs down shadowed alleys, of which there are many, always. Knowing this, it’s a pleasure to spot them.

Father-Issues Ozu

I'm sure Ozu's relationship with his father, who was the 5th generation manager of the family's fertilizer business, was great!

Tokyo Chorus (Yasujirō Ozu, 1931): 3/5

Silent. After some questionable comedy in the first act, the movie settles down into a touching family drama about what happens when a young father with two young kids loses his job. You can tell from Ozu’s 1930s movies that Japan is not doing well, economically.

Passing Fancy (Yasujirō Ozu, 1933): 4/5

Silent. A blue-collar father considers a romantic partner while he struggles to raise his headstrong son, who at 10 or so is already better educated than he is. Is leaving his son to take a job in a remote location the answer to their money woes?

An Inn in Tokyo (Yasujirō Ozu, 1935): 5/5

Silent. A desperately poor, jobless man with two adorable sons struggles to find work and shelter. Again Takeshi Sakamoto. Again a single father. Again an illness. Again the question of whether the father will leave in the end. Again great. Tokyo appears harsh and industrial. Thirteen years later, they would have called this film neo-realism.

There Was a Father (Yasujirō Ozu, 1942): 5/5

A single father sacrifices for his son’s education, but this time there is an odd, unspoken (but familiar, to me) feeling that the father is kind of broken and doesn’t really want to hang out with his child—actually preferring to send him away to school, etc.

Floating Weeds (Yasujirō Ozu, 1959): 3.5/5

One of the best examples of a directors remaking their own movies. (Looking at you Hitchcock and Haneke). A traveling acting troupe returns to the town where one of the actors has a (now grown) son, who doesn’t know the actor is his father. Features a beautiful variation of the idea of a score—often it is as if there is someone in a house nearby playing a flute or tapping a couple of woodblocks together. Strong feelings of grace, serenity, humility—there are disagreements, but everyone is resigned from the beginning that people are going to act the way they want and that life, indeed, goes on.

Gangster Ozu

In each of these, a woman (eventually) serves as the guiding conscience of the gangster, which is also the moral curve of The Godfather. Of course, Kay could never manage to make Michael repent as these men do.

Last Night’s Wife (Yasujirō Ozu, 1930): 3/5

Silent. A father commits a crime to save the family—and must go to jail for it. It was his responsibility to do it and it was his responsibility to pay his dues for it.

Walk Cheerfully (Yasujirō Ozu, 1930): 3/5

Silent. A gang of hoodlums hang out looking cool in their Fedoras, scarves, and long coats—boxing, playing pool, and nicking wallets. The characters have common dances and songs that they casually perform together, as a way to communicate their community (reportedly influenced by Harold Lloyd’s college movies, such as The Freshman). However, the main drama is centered around whether our hoodlum protagonist can give up his thieving ways and become worthy of the woman he has fallen in love with. In this version, he begins his path and penance at the end of act one. In Dragnet Girl, it’s literally in the movie’s last moments. Both are interesting, valid, realistic and satisfying, so why not play out both and discover the difference?

Dragnet Girl (Yasujirō Ozu, 1933): 4/5

Silent. More hats and overcoats, boxing and fistfights, cool guys with nicknames like Eight Card and Mako, and of course one last job. A lot of funny bits using sound. Like: two guys start a fight in the foyer of a restaurant. Cut to the interior of the restaurant and suddenly everyone turns at the same time to see what’s going on off screen. Later, two people in the middle of a conversation suddenly stop and turn toward the door. Someone is knocking. We’re also shown a statuette of the RCA listening dog (registered in the U.S. in 1900).

College/Young Salaryman Ozu

Days of Youth (Yasujirō Ozu, 1929): 3/5

Silent. Ozu’s earliest existing film—a love triangle at a ski lodge (!!). Ozu style is already somewhat present, including some cameras set on the ground so that even when two characters are seated on the ground, the camera looks up to them. Plus, there are some primitive pillow shots (albeit motivated) when the characters gaze out a window.

I Graduated, But… (Yasujirō Ozu, 1929): N/A

Silent. Only 11 minutes of this film survive. A recent graduate has trouble finding a job.

I Flunked, But… (Yasujirō Ozu, 1930): 2.5/5

Silent. The Animal House of its day (although I understand that campus comedies were a trend at this time)—drinking, womanizing and spending more effort to cheat than it would ever take to just learn the stuff. Not very amusing.

The Lady and the Beard (Yasujirō Ozu, 1931): 2.5/5

Silent. A guy grows a big scruffy beard in college—a symbol of his traditional ways. But once he graduates, he has trouble finding enjoyment and a girl. Finally, he shaves the beard and everything’s fine. Meanwhile the women chafe against the arranged marriages that their parents devise. Two measures of modernity vs. tradition.

Where Now are the Dreams of Youth? (Yasujirō Ozu, 1932): 3/5

Silent. When the father of a new graduate dies, the son must take over the his thriving business (including hiring all his goof-off buddies). The chaotic energy is strong in this one, as the modern female is not sweet just bold, and her father is a happy, half naked drunk. Eventually, the “Prince” character must give up his (more traditional) love interest because of his princely duties (as in Lubitch’s The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg and von Stroheim’s The Wedding March), but this time it’s because his friend loved her first and he doesn’t want to be an asshole. This self-consciousness and sensitivity on the part of the prince character is a new path—and very Ozu.

Early Spring, rw (Yasujirō Ozu, 1956): 3/5

A married salary man has an affair. Contains a kiss of passion (although the camera is placed behind the man, so we never see the lips touch). Also contains a scene of post-coital languor. Overall, the movie (Ozu’s first after the success of Tokyo Story) is a real exception to Ozu’s cheerfulness. The young salary men and their wives are all miserable, and having an affair makes it worse. “That’s what we got waiting for us, just disillusion and loneliness. I’ve worked 31 long years to find life is an empty dream.” And I am reminded that Ozu’s gravestone contains only the symbol for Mu (meaning emptiness), which he drew.

Loosies

A Straightforward Boy (Yasujirō Ozu, 1929): N/A

Silent. Only fragments remain of this retelling of O. Henry’s The Ransom of Red Chief, published in 1907. Broadly comic.

Woman of Tokyo - 46 min, (Yasujirō Ozu, 1933): 3.5/5

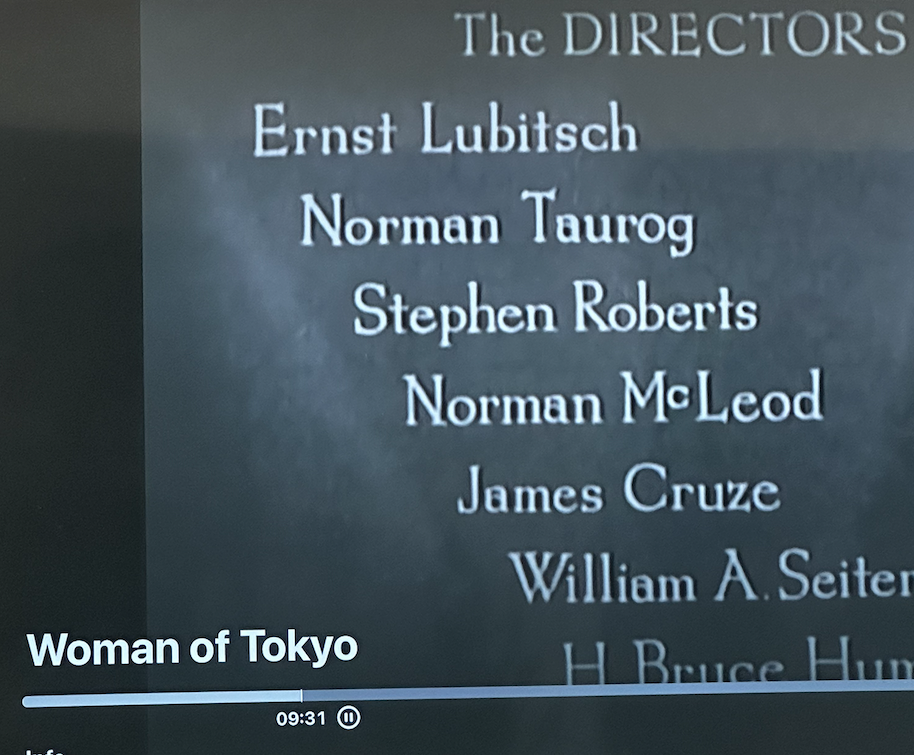

Silent. Sister turns to sex work to pay for her brother’s school. Short but packs a punch, including several violent and emotional confrontations between the characters and a heartfelt tragedy. The characters go see If I Had a Million, a weird omnibus movie directed by Ernst Lubitsch and six other directors. Since that movie has sound, it’s an odd moment when we watch these characters in a silent movie who are watching a sound movie. Ozu gropes toward his classic pillow shots by inserting serenely composed still-lifes of bowls, decorative tables, tea pots.

A Mother Should Be Loved (Yasujirō Ozu, 1934): 3/5

Silent. After her husband dies, the widow must raise her two sons, one of whom is (unbeknownst to him) from her dead husband’s previous marriage. Could be considered part of a “Two Brothers Ozu” series along with I Was Born But..., An Inn in Tokyo, and Good Morning. Or part of a “Single Mother Raises Son” series along with A Hen in the Wind and Record of a Tenement Gentleman.

What Did the Lady Forget? (Yasujirō Ozu, 1937): 4/5

Has a view of marriage not that much different from Hollywood’s screwballs—and it shares with them an unusually (for Ozu) snappy comic tone. When their niece with modern ideas comes to visit from Osaka, it shakes up the marriage of her uncle and aunt, eventually in a good way. Also gives arcs to several other peripheral characters, all in an hour and 10 minutes.

Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (Yasujirō Ozu, 1941): 3/5

Plot-wise, a dry run for Tokyo Story as, after their father dies, three siblings pass the mother and younger sister around in an annoyed way. Ozu likes to start his movies with a crowd scene where all the characters are together (see The Godfather)—as here when the whole family comes together for a photograph.

Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Yasujirō Ozu, 1947): 4/5

A widow reluctantly takes in an orphan child. The tone is lightly comic but ends with some chilling images communicating how many war orphans Japan was dealing with in 1947.

Tokyo Twilight, rw (Yasujirō Ozu, 1957): 3.5/5

Ozu’s most nocturnal film. In fact, with parts of the room out of focus and in pools of light and darkness, it looks nothing like an Ozu film (with the exception of Dragnet Girl), also the subject matter of abortion (evidently legal in 1950s Japan) is by far the most frank and taboo subject in any of his films. Of course that’s one reason to cherish it—but saying it’s your favorite is like saying that Scorsese’s best movie is Kundun. Ozu’s last b/w film.

Some of Ozu’s great actor regulars

Takeshi Sakamoto

Chishū Ryū (featured in 32 of Ozu's films)

Chôko Iida

Setsuko Hara

Ozu the Cineaste

Monday, May 1, 2023

Rifkin's Festival (Woody Allen, 2020): 1/5

I somewhat admire the dedication to churning out shit.